How Does the Clean Power Plan Help US Meet its Climate Targets?

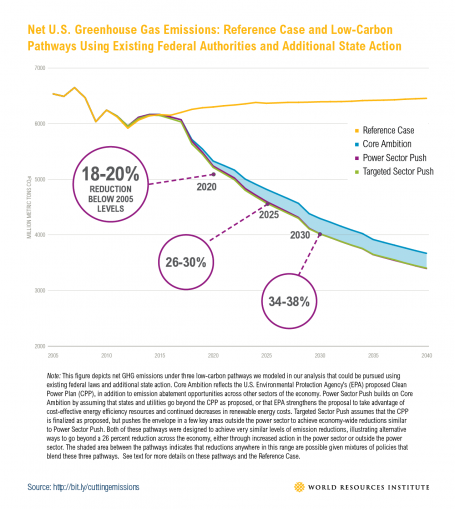

On Monday, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) finalized a strong and flexible Clean Power Plan (CPP) that is expected to reduce power sector emissions 32 percent below 2005 levels by 2030. Together with all the other actions the Obama administration has taken over the last several years, the United States is showing it’s serious about addressing climate change. Notably, businesses and consumers are already making investments to push us further down the low carbon future economy (and many are saving money by doing so). The final CPP is an important step for the United States to meet its 2020 and 2025 emissions-reduction targets, but the nation will need additional steps that continue capitalizing on and accelerating these trends in the power sector and across the economy to achieve those goals.

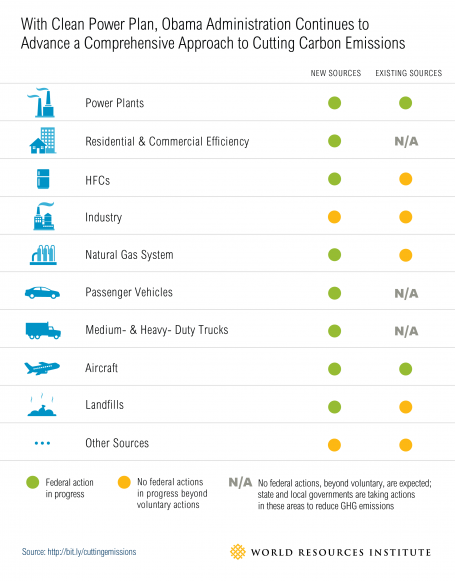

In the WRI paper Delivering on the U.S. Climate Commitment, we found that the United States could meet, or even exceed, its target of reducing GHG emissions 17 percent below 2005 levels by 2020 and 26-28 percent below 2005 levels by 2025 even without Congressional action. While that analysis was based on the proposed CPP, the final version of the Plan achieves similar levels of reductions in 2020 and 2025, leaving that conclusion intact. The final CPP—combined with other recent actions like setting new efficiency standards for commercial rooftop air conditioners, finalizing rules that will reduce emissions of hydrofluorocarbons, and proposing the second phase of its medium- and heavy-duty vehicle fuel efficiency standards—will bend the U.S. emissions trajectory downward, but not enough to hit these targets. The country will need to go beyond the actions taken to date to address carbon dioxide pollution from additional sources and sectors, as shown in the infographic below.

What are the additional opportunities for action?

We’ve identified additional actions this administration (and the next one) can take to help meet its 2020 and 2025 climate targets, including:

- Continuing to ban the use of the most potent hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs), greenhouse gases commonly used as refrigerants, for certain applications and approving climate- friendly alternatives to use in their place. EPA should also extend its existing air conditioning and refrigeration equipment servicing and disposal requirements to cover HFCs, as well as increase initiatives to capture and recycle HFCs from existing equipment to reduce the amount of new HFCs produced.

- Continuing to set new and strengthened efficiency standards for appliances together with voluntary programs to improve building efficiency.

- Swiftly following through on developing carbon dioxide emissions standards for commercial airplane engines.

- Setting ambitious minimum performance standards for industrial equipment along with voluntary benchmarking and labeling programs to encourage further industrial efficiency improvements.

- Addressing both new and existing sources of methane emissions, such as natural gas infrastructure, landfills and coal mines.

- Building on existing voluntary programs to further reduce emissions from other sources, like agriculture, fluorinated gases such as SF6 and PFCs, off-highway vehicles, and nitric and adipic acid manufacturing

- Increase the nation’s carbon sink by increasing forest growth, encouraging the development of urban forests, and conserving sensitive land areas, among other measures.

States and Businesses Can Play a Greater Role

State and local governments and businesses also have an important role to play in helping the United States achieve its GHG reduction targets. This includes enforcing building codes and adopting other efficiency measures; developing urban areas with safe, reliable public transportation and options for biking and walking; and building out more renewable energy.

It’s also in states’ and other actors’ best interests to pursue renewables and efficiency, potentially leading to even greater reductions in the power sector than what the CPP requires. Across the country today, energy efficiency is one of the most cost-effective options that utilities have to reduce emissions. Most states with efficiency-savings targets are on track to meet or exceed their goals, and are saving money for homes and businesses in the process (in fact, state programs that help improve the efficiency of homes and businesses regularly save consumers $2 USDfor every dollar invested, in some cases as much as $5 USD). New wind and solar energy is becoming increasingly cost competitive with coal and natural gas in many parts of the country, with some utilities investing in renewable energy beyond what their state requires because it is economical to do so (research actually shows that increased renewable energy generation has the potential to save American ratepayers in some regions tens of billions of dollars a year over the current mix of electric power options). Businesses across the country are alsodemanding increased access to renewable energy.

And EPA has improved its final CPP to further incentivize states to invest in renewable energy and energy efficiency by offering extra credits to those states that invest in these sources in the two years before the rule’s implementation period. The flexible CPP framework will enable cost savings for Americans, job creation, and improved public health in addition to emission reductions. The rule is expected to avoid up to 3,600 premature deaths, lead to 90,000 fewer asthma attacks in children, create tens of thousands of jobs, and save consumers $155 billion from 2020 to 2030.

If the push toward increased use of renewables and efficiency continues, and states and businesses continue to innovate and go beyond what is required by law, then the United States could achieve more reductions from the power sector than what we assume in our analysis. This would lower the reductions needed from other sectors, making it easier for the country to meet its 2020 and 2025 reduction targets.