The Good, the Bad and the Urgent: MDB Climate Finance in 2020

Multilateral development banks (MDBs) play an important role in financing developing countries’ efforts to reduce emissions and protect against the effects of climate change, and 2020 was a critical waypoint for MDB climate finance. For one, it marked the due date for the climate finance targets many MDBs set in 2015. 2020 was also the year by which developed countries committed to mobilize $100 billion per year in climate finance for developing countries, with many developed countries channeling a significant share through MDBs.

Unfortunately, MDB climate finance for developing countries fell by almost 5% in 2020 compared to 2019 (or down by 2.2% including finance from the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), which was added to the report for the first time in 2020), and coronavirus response efforts prevented most MDBs from meeting their own 2020 climate finance targets.

As we’ve done in past years (see 2016, 2017, 2018, 2019 editions), we analyzed MDBs’ 2020 Joint Report on Climate Finance to draw out key takeaways beyond this headline. Here’s a look at the good, the bad and the urgent findings.

(Note: Since their 2019 joint report, MDBs changed the way they classify countries, making it more difficult to assess how their climate finance contributes to the $100-billion-a-year goal set under the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (see box). Where possible, we adjusted figures to align with the previous categorization of developing countries.)

The Good:

1. Most MDBs set post-2020 climate finance targets.

With the exception of the New Development Bank (NDB), all the major MDBs have now set post-2020 climate finance targets. While the targets reflect varying levels of ambition, the adoption of new targets signals the continuing importance of MDBs’ role in meeting global climate finance needs.

In a welcome development, the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) and the Islamic Development Bank (IsDB) adopted climate finance targets for the first time.

NDB should adopt a post-2020 climate finance target as soon as possible, while other banks should strengthen theirs. The Inter-American Development Bank Group (IDBG), for example, adopted a target that holds climate finance steady at the top end of its pre-2020 targeted range. MDBs need to increase their targets — not decrease or maintain them.

MDBs’ Climate Finance Targets

| MDB | Pre-2020 Target | Post-2020 Target |

|---|---|---|

| afDB | 40% of approved finance per year by 2020 | At least $25 billion for 2020-2025 |

| ADB | $6 billion by 2020; $4 billion for mitigation and $2 billion for adaptation | $80 billion for 2019-2030, and 75% of projects (by number of projects rather than amount of financing) by 2030 |

| AIIB | None | 50% of annual loan volume by 2025 (aiming to reach $10 billion in total annual loan volume by 2025) |

| EBRD | 40% of annual commitments support environment/climate financing by 2020, providing $20 billion for 2016-2020 | More than 50% of commitments support green finance by 2025 |

| EIB |

Global: $20 billion per year for 2016-2020, equal to at least 25% of overall lending

Developing countries: 35% of total lending in those countries by 2020 |

Global: 50% of operations support climate action and environmental sustainability by 2025; €1 trillion (around $1.18 trillion) of investments in climate action and sustainability from 2021-2030

No developing country specific target yet |

| IsDB |

None |

35% of overall annual lending by 2025 |

| IDBG | 25-30% of commitments by 2020 | At least 30% of finance from IDB, IDB Invest and IDB Lab (the three components of the IDB Group) for 2021-2024 |

| NDB | None | None |

| WBG | 28% of annual commitments by 2020 | 35% of overall financing from 2021-2025; 50% of IDA and IBRD climate finance to support adaptation and resilience |

2. Some banks took important steps toward transparency and accountability.

For example, in 2019, AIIB provided only partial reporting on its climate finance. In the 2020 report, AIIB implemented the joint MDB climate finance tracking methodologies and reported complete climate finance figures.

NDB reported certain climate finance figures for the first time this year and plans to extend its application of the climate finance tracking methodologies in years to come. It should begin reporting alongside its peer institutions as soon as possible, as it is the only remaining major MDB that has yet to do so.

3. Adaptation finance maintained a stable share of climate finance, despite COVID-19.

Finance supporting adaptation in low- and middle-income economies increased slightly, from 34% of MDB climate finance in 2019 to 35% in 2020, in part indicating that resilience remained a priority despite the focus on pandemic response. It may also suggest that resilience was integrated into emergency response measures.

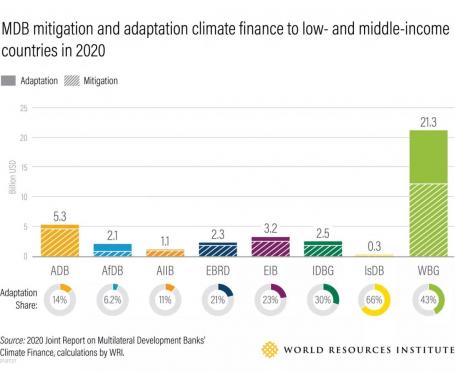

This follows the promising rising trend of the last five years, as adaptation represented only 20% of MDB climate finance in 2015. Adaptation finance has notably represented over half of the AfDB’s climate finance for two years in a row, and the IsDB jumped from 40% of its climate finance supporting adaptation in 2019 to 66% in 2020.

Adaptation costs nonetheless continue to outpace available funds, and the Paris Agreement calls for a balance in climate finance between mitigation and adaptation. MDB adaptation finance will need to increase rapidly to meet adaptation financing needs in developing countries.

The Bad:

1. Climate finance for developing countries fell in 2020.

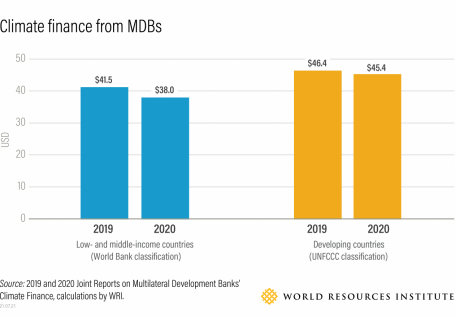

Total climate finance to low- and middle-income economies ($38 billion) fell by $3.5 billion (8.4%) from 2019 to 2020, and finance to UNFCCC-defined developing countries ($45.4 billion) by $1 billion (2.2%). This drop comes despite the inclusion of $1.2 billion of climate finance from AIIB, which wasn’t included in 2019 totals.

This troubling reversal comes at the worst possible moment, as there are already widespread concerns that developed countries have been unable to meet their $100-billion-a-year commitment, much of which flows through MDBs. A decline in climate finance through MDBs would require developed countries to provide even more through other channels (such as through bilateral aid and climate funds like the Green Climate Fund) to meet the goal.

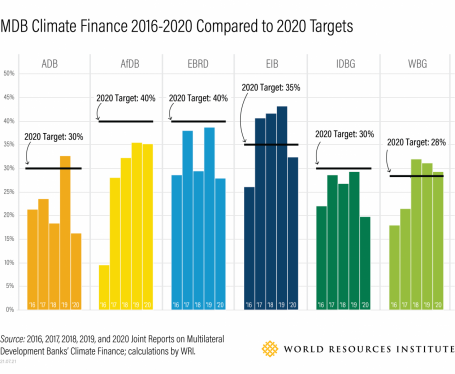

2. As MDBs helped member countries respond to the coronavirus pandemic, most failed to meet their 2020 climate finance targets.

To some extent, this result is understandable. Some emergency responses, including budget support or investments in healthcare systems and unemployment assistance, have only limited direct climate relevance. However, some banks may have missed opportunities to integrate climate into their COVID-19 response measures.

Because of the unprecedented circumstances, some banks reported on the climate finance share of operations excluding coronavirus response projects. For example, without COVID-19 response operations, climate finance reached 44% of AfDB’s overall financing, 30% of IDBG’s and 25% of ADB’s.

3. Private co-finance dropped.

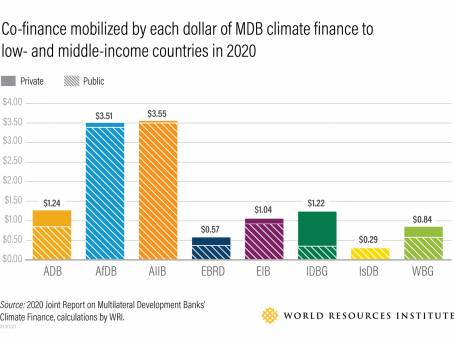

As part of their “Billions to Trillions” agenda launched in 2015, MDBs put significant emphasis on using public funding to mobilize orders of magnitude more private co-finance. The theory was that by “derisking,” or subsidizing riskier parts of deals with various types of financial instruments (for example, concessional loans, equity or guarantees), MDBs could attract private finance to projects they wouldn’t have otherwise invested in, thereby raising more money than otherwise possible. Yet MDBs have continually struggled to achieve this goal.

Private co-finance rates fell for the second year in a row: For every dollar MDBs invested in climate finance in 2020, they reported just $0.29 in co-financing from private sources. Even the most successful MDB for private co-financing in 2020, the IDB, did not exceed one dollar in private capital for each dollar it invested.

(Conversely, some MDBs report greater amounts of co-financing from other public sources, such as money from recipient country governments and developed country aid agencies. AfDB and AIIB reported more than $3 in other public finance for each dollar they put up.)

The failure to mobilize private finance predates the COVID-19 pandemic. The Billions to Trillions agenda is more accurately delivering billions to billions, especially as MDBs continue to rely heavily on loans instead of making greater use of equity and guarantees — an issue we raised in our first article in this series. As it begins its seventh year of implementation with consistently disappointing figures, and with growing critiques of the “derisking” approach, it is past time for MDBs to explore whether other approaches to promoting private investments in climate action — including regulation to create more attractive climate investment conditions — may be more effective.

The Urgent:

1. MDBs now face the urgent task of rapidly scaling up climate finance to make up for lost ground in 2020.

In 2020, MDBs were rightly focused on meeting their members’ immediate emergency response needs. However, many potential recovery measures offer clear opportunities to support climate mitigation or adaptation. As the MDBs support ongoing coronavirus response and economic recovery efforts, they must also maximize climate-related co-benefits through a green recovery.

CORRECTION, 8/2/21: A previous version of this article incorrectly stated that total climate finance to low-and middle-income economies ($36.89 billion) fell by $4.6 billion (11%) from 2019 to 2020, and finance to UNFCCC-defined developing countries ($44.2 billion) by $2.3 billion (4.95%). We have since corrected the piece to reflect the fact that total climate finance to low- and middle-income economies ($38 billion) fell by $3.5 billion (8.4%) from 2019 to 2020, and finance to UNFCCC-defined developing countries ($45.4 billion) by $1 billion (2.2%). We regret the error.