South Korea and Japan Will End Overseas Coal Financing. Will China Catch Up?

Since 2013, public finance from China, Japan and South Korea accounted for more than 95% of total foreign financing toward coal-fired power plants. This financing enabled the construction and operation of coal power plants in developing countries, where investment in power supply does not match demand. These investments also came at a time when the global carbon budget was already overstretched.

At the Leaders Summit on Climate, South Korea made headlines by announcing it will immediately stop state-backed overseas coal finance. Four weeks later, Japan finally joined the other G7 countries to commit to end international coal financing by the end of 2021. While China is moving in the same direction by transitioning their international financing, it is now the only nation among the three largest providers of foreign coal finance without a formal commitment to end overseas coal finance.

It’s time for China to explicitly exit the sector. If the world is to reach carbon-neutral goals and prevent the worst impacts of climate change, no new coal investment can happen. It’s not just a moral argument — financially, coal investments are becoming less attractive than ever. With both of these dynamics in play, developing countries are less interested than ever in coal power.

Why Are Potential Hosts Turning Away from Coal?

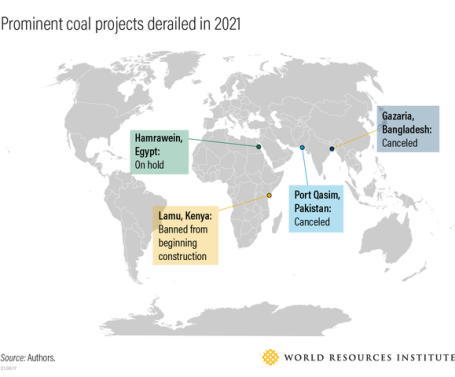

Excluding China, global coal power capacity slowed to its lowest net increase in 2020, and President Xi suggested at the Leaders’ Summit that China would more strictly control domestic coal growth through the rest of the decade. Many coal power projects were cancelled or shelved, including some that Chinese companies planned to build or finance. Additionally, some Southeast Asian, South Asian and African countries that previously focused on coal power development decided to pause coal power.

The question is, why are host countries losing interest in coal? Three interrelated factors explain:

1. Environmental and social permitting is more stringent.

Resistance from local communities and civil organizations led to many coal-fired power projects failing to acquire permits needed to push forward, leading to project delays and even cancellations. These dynamics have been a key factor in Vietnam considering to stop building new coal power.

2. The COVID-19 pandemic is reshaping domestic energy markets.

In most developing countries in South and Southeast Asia, the drop in electricity demand caused by the pandemic, such as reductions in services and lockdowns within industry, left governments with large, running bills fixed on their coal capacity tariffs. These governments had to pay those bills regardless of actual power generation. Coupled with highly impacted economies, the unsustainable situation triggered countries like Indonesia and Pakistan to consider the use of coal power. It is unlikely that countries will continue a coal-reliant path after the pandemic now that a long-existent structural challenge — coal power’s inability to adjust to volatile demand — has been exposed.

3. Coal is becoming more expensive

Coal power projects rely on heavy capital investment when counting in the associated transportation and storage facilities, and the increasing environmental costs from water usage and carbon trading. The costs of new coal-fired power plants are already higher than new renewable plants in 35 countries, including Pakistan, Bangladesh, Indonesia, the Philippines, Vietnam, Malaysia and Turkey. This is leading to a foreseeable phase-out of the international coal finance supply.

Time For China to Catch Up and Solidify a Roadmap

With South Korea and Japan putting an end to overseas coal finance and developing countries losing interest in coal, China should be next to make a commitment — and it is signaling movement in that direction.

In a joint statement the United States and China released in April 2021, China pledged to maximize its overseas investment to support the transition from fossil fuel to renewables. This is an important step toward aligning China’s outbound investment with the Paris Agreement, and fulfilling President Xi’s commitment to a green Belt and Road Initiative. China should elaborate on this high-level commitment in an action plan for China to quit overseas coal financing, both public and private.

China has been by far the largest financier for overseas coal projects. While losing this business might be painful, missing out on renewables by hesitating on the energy transition would be significantly worse.

Recent moves from Chinese policy makers and stakeholders illustrate what a national commitment to phase out coal might require. Important milestones China must reach to end overseas coal finance include:

1. Proactive responses to explicit requests from host countries.

In a recent case from Bangladesh, the Chinese Embassy made it clear that China will no longer consider coal mining and coal-fired power stations in the country. The Bangladesh finance ministry sent a request to the Chinese Embassy to cancel two coal-related projects from a past bilateral investment memorandum of understanding (MOU), which the embassy agreed to do. Revisiting what to finance in this manner can happen elsewhere, particularly considering increasing coal phase-out trends.

2. Institutionalizing coal phase-out in outbound investment.

In April 2021, the Deputy Governor of the Central Bank of China said China will stringently regulate overseas coal financing. This is reflected in the updated Green Bond Taxonomy that the People's Bank of China (PBOC) and two other ministries published in April 2021. Coal and other fossil fuel power projects, domestic and overseas, will not be eligible to use the proceeds from a green bond.

Regulators who oversee outbound investment daily can also effectively shift financial flows away from coal, especially through an exclusion list. Both the industrial authority and the supervisor of state-owned enterprises (SOEs) — the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) and the State-Owned Assets Supervision and Administration (SASAC), respectively — can add coal projects to their sensitive or negative list. This can prevent SOEs and other Chinese investors from financing the sector. These regulatory and supervisory attempts prepare institutions to be ready for a wider national commitment.

3. Corporate shifts from coal to renewable energy.

Driven by China’s carbon neutrality goal and the growing overseas market need for renewables, some traditional coal power builders in China have begun to transition their businesses. For example, typical coal power builder and investor Datang extended its business in overseas renewables. China’s five biggest centrally-owned power generators are all rolling out plans for the very near carbon-neutral future ahead of schedule, featuring increased capacity in clean energies. These plans should integrate overseas investment as well.

Seizing the Opportunity to End Overseas Coal Finance

COP26 President Alok Sharma, UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres and IEA President Fatih Birol are among the voices to recently urge the world to quit coal immediately, and with good reason: Achieving the global transition to a net-zero GHG emissions future will require a consistent, thorough policy framework for ending overseas coal finance.

As the last three nations to fund overseas coal finance, South Korea, Japan and China’s actions to step away from coal financing will be instrumental in executing this transition. Doing so could also free up international financing resources to support renewable power projects, which are also necessary to reach net zero by 2050 and could meet development and climate needs in developing countries.