Drop by Drop, Better Management Makes Dents in China’s Water Stress

With more than one-third of its land area facing high or extremely high water stress, China is working hard to match growing demands for freshwater with the available renewable supply. The government is well aware of the threats that water stress can pose—economic stagnation, the demise of water-dependent industries, and conflicts over resources.

In 2012, the Chinese State Council issued an administrative guidance document, “Opinions of the State Council on Applying the Strictest Water Resources Control System,” to address growing water challenges. The document, commonly referred to as the “Three Red Lines,” requires stricter management of water resources in three ways: by capping annual water usage at 700 billion cubic meters for the overall economy by 2030, increasing irrigation efficiency, and protecting water quality. Following the central government’s step, sub-national governments have set up their own more detailed goals.

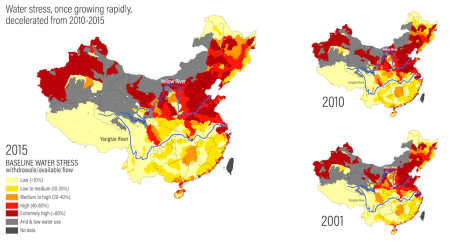

Have these “Three Red Lines” improved China’s water security? WRI used data on water withdrawal for three years (2001, 2010 and 2015) to determine changes in water consumption over time. The rate of increase in China’s water withdrawals has significantly slowed, from 5.1 billion cubic meters per year in 2001-2010, to 1.6 billion cubic meters per year from 2010-2015. But local circumstances differ from the overall picture: certain geographies in China are still experiencing rapidly increasing stress.

Tracking Water Stress in China

WRI experts mapped and analyzed China’s Baseline Water Stress for 2015 to identify trends, worsening conditions and improvements. Baseline Water Stress is defined as the total annual water withdrawals (municipal, industrial and agricultural) as a percent of the total annual available surface water. High values indicate more competition among users—a value above 40 percent is considered as “high water stress,” and above 80 percent as “extremely high.”

This analysis uses WRI’s Aqueduct methodology and the NASA GLDAS global hydrologic model to assess long-term averages for renewable surface water supply, and detailed sectoral water demand data reported by the Chinese government. As is true for many countries, there is no independent verification of these self-reported demand figures. We are, therefore, relying on the accuracy of the government-reported data without the ability to check them against other sources. Based on these data and the related analyses, we observed a number of trends:

The Bad News

- The overall pattern of water stress has remained consistent from 2001 to 2015. Northern China experiences more stress than Southern China. Compared to 2010, the total area of China experiencing high and extremely high water stress did not change in 2015, as the “Three Red Lines” policy took effect.

- The population living in high or extremely high water stress areas increased by 3 percent from 2010-2015. Compared to 2001-2010, areas at the upstream reaches of the Yellow River and Yangtze River both had less water stress, while areas at the downstream reaches of the Yellow River had worse water stress, as people began to move downstream.

The Good News

Although water stress in China worsened from 2001 to 2010, driven largely by increased water demand across sectors, water stress maps of 2015 show that the situation appears to be improving in many areas:

-

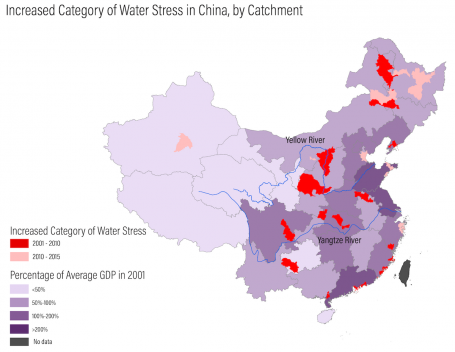

Worsening water stress is slowing down. In a recent five-year period (2010-2015), the growth in areas experiencing higher water stress slowed; the total area with worsened water stress from 2010-2015 was only 35 percent of the previous ten-year period (2001-2010).

-

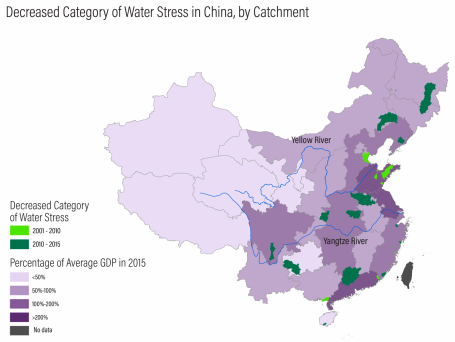

More areas are improving. The number of areas experiencing a decrease in water stress from 2010-2015 was 9 times greater compared to the 2001-2010 time period.

- Stress declining in Central China. As evidenced by the maps above, there are broad disparities within and between China’s various provinces. Water stress increased in central China’s provinces from 2001-2010, keeping pace with rapid regional economic growth over this same period. Since 2010, water stress levels have begun to decline in some catchments as sectoral reductions in water withdrawals have taken place.

These positive developments can be seen at the local level. For example, industrial water withdrawals in Panzhihua, in the Sichuan Province in southwest China, decreased by 31 percent in 2015 compared to 2010. This change was driven by incentives put in place by the Panzhihua Municipal Government, which aimed to decrease the water use per unit of industrial value added by 30 percent in 2015 compared to 2010. In Panzhihua, 37 industrial companies were enrolled in Sichuan’s “Hundred Companies Water Saving Working Plan” issued in 2013, which targets a total of 546 companies in the province whose water withdrawal exceeds 300,000 cubic meters per year and accounts for nearly 70 percent of total industrial water withdrawal in Sichuan. The Working Plan’s focus is to “control the increment, adjust the existing, phase out the outdated” to increase water efficiency. In 2013, water withdrawal from these 37 companies decreased by 22 percent compared to previous year, with a 85.40 percent reuse rate. It seems that the Three Red Line regulations and local government policies and incentives are having an effect.

Hope for Three Red Lines

These analyses clearly suggest that China has begun to see the positive impacts of stricter management of water resources. Although there are differences across regions—with some experiencing worsened stress—the average overall situation has improved since issuance of the “Three Red Lines” policy, including at the sectoral level.

Since the analysis is based on only two data points (2010 and 2015), it is not clear if this is a trend or just a blip in the data. If this trend bears out over time, it will demonstrate that even relatively water-stressed countries with booming economies can improve their situations through meaningful public policies and well-aligned incentives.